Motor racing threw up some notable writers. SCH Davis, Bentley Boy of the 1920, sports editor of The Autocar over 40 years. Rodney Walkerley, his urbane, witty opposite number at The Motor. Bill Boddy, longest serving editor of Motor Sport; Denis Jenkinson its Continental Correspondent and co-pilot with Moss in the Mille Miglia. Gregor Grant, Autosport founder who never let the facts stand in the way of a good story. The engaging American Henry B Manney III, as funny in life as in print. Peter Garnier, Davis’s astute successor, so close to his subject they made him secretary of the Grand Prix Drivers’ Association. Innes Ireland, amazingly articulate and perceptive at Autocar, paving the way for television punditry from James Hunt, Martin Brundle and David Coulthard. Elegant technicians, Laurence Pomeroy son of the gifted Vauxhall designer and LJK Setright, whose classical quotations were almost as good as Pom’s but whose engineering was no match. We had the well-informed David Phipps and nowadays Alan Henry and spirited prose from Maurice Hamilton and Peter Windsor.

Yet none of them were quite a match for the best news-gatherer the sport ever had. Ill-health has consigned Eoin Young to a hospice in his native New Zealand but his From The Grid column in Autocar was obligatory for anybody in the business or out of it. Well-connected ever since he came to Europe and worked with Bruce McLaren in 1961 Eoin had the biggest scoops. His was the best-informed commentary, nobody knew as much as he, nobody spilled as many secrets and above all his writing told readers he was the insider’s insider. It didn’t matter if you were an outsider, Eoin had a way of gaining your confidence.

Eoin Young knew who was going to drive for whom next year – sometimes before they did. He knew who was up-and-coming and who was going down-and-out. He would take notes and print it yet I don’t suppose he ever broke a single confidence. If you told Eoin anything he would take it that you were, in effect, telling the world. He was only the means to the printed page. His veracity seemed to encourage his informants, who told him things they’d confide to no-one else.

Maybe a little rancorous in later years - his personal life was turbulent – Eoin was competitive and neither gave nor expected anything less than determined bargaining in books. His Autocar columns will be a priceless resource to motor racing historians, his books perhaps less so. They were variable; he seemed to grow bored with research or writing at length or in depth. His forensic skills were best in his brief, punchy impertinent style.

Thursday 28 August 2014

Tuesday 26 August 2014

Spa-Sofia-Liège: A motoring adventure

Fifty years ago this week I set off from Spa in Belgium to report the last Spa-Sofia-Liège Rally. The Marathon de la Route was organised by the Royal Motor Union of Liège, whose M Garot enjoyed his reputation for organising the toughest rally in the world. Started in 1931 as the Liège-Rome-Liège, it had been to various turning points, settling in 1964 on Bulgaria then well behind the Iron Curtain. Only a handful of cars ever made it to the finish.

I set off from Spa in pursuit. The Motor sent junior staff on important assignments safe in the knowledge that they were accompanied by veteran photographers. They, like George Moore who came with me, had done it all before. We could pitch up at a Yugoslav B&B; George would know the language, how much we’d be charged and probably the proprietor’s name. He introduced me to drivers, team managers, other journalists and helped me across the tripwires of providing a true and accurate account, without frightening the horses.

You would be meeting them again on the RAC and then the Monte as well as next year’s Alpine. They seemed to run out of Presse plates so I ran as an Officiel.

A Ford Corsair GT was unlikely as a means of keeping up with works Austin-Healey 3000s and 1962 European Rally Champion Eugen Böhringer, but it was the only car spare. It could manage 95mph on a good day and reach 60 inside 13sec. In the interests of science I made the brakes fade on the downside of an alp; I had heard about brake fade but never really experienced it so when George dozed off I got the brake fluid boiling. The 9in front discs (there were drums at the back) were probably aglow. I left off before it got dangerous.

We kept up with the rally for 3,000 miles. George knew the shortcuts when it dashed off into the mountains. Memorably this was the event on which Logan Morrison and Johnstone Syer, whom I knew from Scottish rallies, retired their works Rover 2000 when Blomquist’s Volks-wagen overturned. The driver was unconscious and nobody, not even a VW team-mate, had stopped so Logan's opportunity for glory was lost.

This was also the rally on which BMC competitions manager Stuart Turner could not conceal his delight. He had not only scored the second win with a big Healey but also “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.”

Title of the report? The Beatles had just made “A Hard Day’s Night.” Aaltonen’s car (below left) was sold by Bonhams in 2005 for £100,500. I drove another works car in 1966, reporting on it in Safety Fast magazine and again in Sports Car Classics Vol 1. Amazon £3.08. After a number of countries decided rallies at such speeds dangerous, they refused the Royal Motor Union permission to continue it. The Marathon de la Route became a track event on the Nürburgring. The Liège-Rome-Liège reappeared only as a touring classic.

The Motor, week ending September 5 1964

A hard (four) days’ night. Austin-Healey win an even faster Spa-Sofia-Liège rally. Report by Eric Dymock pictures by George Moore.

“The Liège has been getting slack; there were twenty five finishers last year and eighteen the year before.” In 1961 there were eight, thirteen in 1960 and fourteen the year before that. M. Garot wants it back to about eight and this year he very nearly got his wish until an alteration in plans put several cars back into the running. But he tried.

After the finish, John Sprinzel said, “This year we did about a day and a half's route in a day.” The pace was much, much hotter with average speeds of 50 and 60 mph over rough, rocky roads where such a schedule is just not possible. The 1964 Spa-Sofia-Liège was run in hot weather over roads little rougher than before but at a cracking, damaging pace for four days and nights of the most intensive high-speed motoring in the world.

RaunoAaltonen, the Finnish speedboat racer and Tony Ambrose, Hampshire shopkeeper, won with a works Austin-Healey 3000. Saabs driven by Erik Carlsson and Pat Moss-Carlsson were second and fourth, and Eugene Böhringer took third place in a 230SL Mercedes-Benz after two successive wins in 1962 and 1963. For finishing in three consecutive years, Böhringer wins a Gold Cup in company, this year, with Paul Colteloni (Citroën), Francis Charlier (Volvo) and Bill Bengry (Rover two years, now Sunbeam).

Citroën were the only manufacturer with a team left intact (they had entered three) and none of the club teams finished with more than two runners. Forty-two tired, dusty people steered twenty-one tired, dusty, battered motor¬cars into the finish on Saturday, survivors of the hundred or so gleaming machines which left Belgium late the previous Tuesday. Three Alfa Romeos were entered; none finished. Thirteen Citroëns were entered; only four sighed and wheezed into the last control. Out of eighteen Fords only three survived and the entire Triumph, Renault and Rover teams were. wiped out. Volks¬wagens, usually stayers on rough courses, started with seven, finished with one; even the might of Mercedes was reduced from five to two, although two more struggled on till the very last night.

The scrutineering on Tuesday morning was a leisurely affair, and nothing caused much trouble. As last year, there was some carping over lights, the officials preferring paired spot lamps and reversing lights worked by the gear 1ever and not a switch. So while they appeared not to notice Perspex windows and plastic body panels, they banned an odd fog light. Drivers solemnly removed the bulbs, the officials daubed paint here and there, stamped the car and it was over -¬ except for the replacement of the bulbs just down the road. All very casual. One British team chief wryly remarked “You could drive up here in a supercharged plastic van and they'd pass it”.

The cars were despatched from Liège on Tuesday evening (with the exception of eight non-starters including Trautmann (Lancia) and Feret’s Renault) in quick, three-minute batches of three to spend the night on the Autobahn through Germany, arriving just after first light at Neu Ulm, beyond Stuttgart. The section was neutralized for time, but it was here that Rover's misfortunes began. Anne Hall handed over the 2000 to co-driver Denise McCluggage who, while Anne slept, wrong-slotted down the Stuttgart Auto¬bahn and went 100 kilometres before she realized her mistake. The hour’s lateness guillotine swept down on the Rover before the event was properly under way.

Through Austria, and into northern Italy over the Passo di Resia to the Passo di Xomo, the rally began in earnest. High average speeds were imposed over the dusty, narrow roads, which climbed close to the peaks in everlasting hairpin bends. And the retirements began. The Boyd/Crawford Humber went out before the Alps, so did the Michael Nesbitt/Sheila Aldersmith Mini-Cooper, at Lindau with a broken fan pulley. High in the Alps, at Tresche-Conca the pace and the sun were both hot and tourists coming the other way, through the control at Enego were picking their .way carefully. But enthusiastic Italian policemen waved the rally cars through villages and the popu¬lation joined in urging the drivers to greater things. If the rally was momentarily unpopular with other cars actually on the road, bystanders in those high-altitude villages loved it. (Below: My 1966 works car on test)

By Villa Dont, just before the Yugoslav border, the WiIlcox-Smith Saab retired, the Xomo had claimed an Italian-entered Maserati, and some really punishing sections began. By the time the rally had entered Yugoslavia and passed through Bled, Col and Carrefour Ogulin in the early hours of Thursday morning the pace was telling very seriously. Ford's troubles began with the Richards/David Cortina going out, followed by the Ray/Hatchett Cortina. The Martin Hurst/Bateman Rover 3-litre retired after a stone damaged the fan, which disintegrated through the radiator. The car lost its water and that was that. The Belgian Harris/Gaban Lancia Flaminia, de Lageneste/du Genestou in their works Citroën, the Wilson/Smith Renault, and the Slotemaker/Gorris Daf, were among the 25 cars this 150-mile stretch of rocky, dusty road claimed. Timo Makinen had persistent tyre trouble; six punctures in quick succession losing him so much time he had to retire and another works Citroën went out with clutch trouble. Both American Ford Mustangs retired on this stretch, one overturned.

Novi, on the coast, Zagreb and the autoput to Belgrade then took their toll. The weather remained hot, wearing out tyres and brakes fast, as well as the drivers. The high speeds on the autoput overheated the gearboxes on the heavily undershielded works M.G. Bs of Pauline Mayman/Valerie Domleo and Julian Vernaeve/David Hiam; both broke before Belgrade. The Clark/Culcheth Rover 2000 stopped with engine trouble and the Marang/”Ponti” works Citroën retired. Many, many cars were now running very late and just before the Bulgarian border the organizers intro¬duced a change of route. This added a loop of fairly easy road about 90 kilo¬metres long, with which went a two-hour time allowance. Whether M. Garot did this to give the drivers some breathing space or not, this was in effect what happened and probably more cars reached the finish as a result. Certainly, the original route was passable (some used it) and service crews at Sofia, the turning point, were glad of the extra few minutes to restore the battered cars to something nearer rallyworthiness.

But Bulgaria claimed its victims too. Renault lost two R8s and Austin-Healey the Paddy Hopkirk/Henry Liddon car, which broke down also with gearbox trouble. Honda, after their tragic Liège last year, had entered one car with a Belgian/Japanese crew, but it, too retired when it was hit by a lorry. The Seigle-Morris/Nash Ford Corsair went out at Sofia and so did one of the big rear-engined Czechoslovac Tatras.

The survivors now attacked one of the roughest parts of the entire rally. Back into Yugoslavia through Kursumlija to Titograd and Stolac. The King/Marlow Ford Cortina (a private entry which usually gets further than most) went out near Titograd after the electrics failed and the car had to be push started at every control. A puncture when the time allowance was running out was the final blow. The Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina's front suspension was getting tattered by now and needed frequent attention. Help was recruited from the most unlikely sources to weld and rebuild for a harrowing but apparently hilarious limp to the finish.

The Taylor/Melia works Cortina finished, its rally on the same road, or rather off the same road too badly damaged to continue. SimiIarly the Elford/Stone works Cortina crashed with its wheeIs in the air and the James/ Hughes Rover 3-litre stopped against the rocks, thus sacrificing two gold cups. All the accidents were without serious injury to the drivers.

The Gendebien/Demortier Citroën re¬tired less spectacularly but just as effectively with distributor trouble, then it was the turn of the works Triumph 2000s to fail. They had been going very strongly indeed up to Stolac and Split on the return through Yugoslavia, especially the Terry Hunter/Geoff Mabbs car. The Fidler/Grimshaw and the Thuner/Gretener cars went out first, then the third at Split, all within a short dis¬tance of one another with the rear suspension breaking loose. Logan Morrison/Johnstone Syer retired their works Rover 2000 when they went to the help of the Blomquist/Nilsson Volks¬wagen which had overturned. The driver was unconscious and no other help was available (nobody else, not even a VW team-mate had stopped) so Logan's chances went with another car's acci¬dent. The last Rover (the Cuff/Baguley 3-litre) retired, running out of time after hitting a wall near Split. The Toivonen Volkswagen went out with a broken gearbox.

At Obrovac, the rally had spread itself out over many miles of road. The sur¬vivors who were motoring strongest in the intense heat were being led by the Aaltonen/Ambrose Austin-Healey and Böhringer/Kaiser Mercedes-Benz 230SL, bent now and losing oil. The two Saabs were crackling their fierce exhaust notes through the tiny Yugoslav villages watched by wondering peasants and only Ewy Rosquist looked cool at the wheel of the Mercedes-Benz 220SE she co-drove with Schiek, The long, straggling field drove up the twisty, spectacular, but well¬ surfaced coast road beside the inviting Adriatic and back into the Italian Alps for the second time and the final, gruelling night’s drive. Further casualties were few; there weren’t many cars left to drop out and those who had motored thus far were very determined indeed. A Belgian Mercedes-Benz 220SE failed at Bienno and the similar works car of Kreder and Kling at Trafoi.

The finish was almost an anti-climax. Large crowds and flowers greeted the dusty, battered, straggling cars as they creaked into Spa before the final proces¬sion to the Royal Motor Union premises in Liège itself. Past winner Pat Moss and her pert, pretty 19-year-old Swedish co¬driver Elizabeth Nystrom got a special cheer. The winning Austin-Healey looked little the worse for its ordeal and so did the Saabs. Böhringer's Mercedes had lost some front lights. The brave La Trobe/Skeffington Humber Super Snipe whose, performance had been staggering had a dented door; the big, yellow Tatra V8 which had done equally well (such big cars must have been a handful) was similarly bent. The Alan Allard/Mackies Cortina was scraped on all four corners, after an off-the-road excursion on its roof, and the Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina limped into the finish using up so much of its time allowance that all the crowds had gone home and no one saw its bruises.

What pleased B.M.C. team manager Stuart Turner almost as much as his out¬right Austin-Healey win? “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.” The Wadsworth/Wood Morris-Cooper was, in the final pare fermé in Belgium, albeit with heavy penalties, but after some 3,100 of the world’s toughest, roughest, fastest miles.

I set off from Spa in pursuit. The Motor sent junior staff on important assignments safe in the knowledge that they were accompanied by veteran photographers. They, like George Moore who came with me, had done it all before. We could pitch up at a Yugoslav B&B; George would know the language, how much we’d be charged and probably the proprietor’s name. He introduced me to drivers, team managers, other journalists and helped me across the tripwires of providing a true and accurate account, without frightening the horses.

You would be meeting them again on the RAC and then the Monte as well as next year’s Alpine. They seemed to run out of Presse plates so I ran as an Officiel.

A Ford Corsair GT was unlikely as a means of keeping up with works Austin-Healey 3000s and 1962 European Rally Champion Eugen Böhringer, but it was the only car spare. It could manage 95mph on a good day and reach 60 inside 13sec. In the interests of science I made the brakes fade on the downside of an alp; I had heard about brake fade but never really experienced it so when George dozed off I got the brake fluid boiling. The 9in front discs (there were drums at the back) were probably aglow. I left off before it got dangerous.

We kept up with the rally for 3,000 miles. George knew the shortcuts when it dashed off into the mountains. Memorably this was the event on which Logan Morrison and Johnstone Syer, whom I knew from Scottish rallies, retired their works Rover 2000 when Blomquist’s Volks-wagen overturned. The driver was unconscious and nobody, not even a VW team-mate, had stopped so Logan's opportunity for glory was lost.

This was also the rally on which BMC competitions manager Stuart Turner could not conceal his delight. He had not only scored the second win with a big Healey but also “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.”

Title of the report? The Beatles had just made “A Hard Day’s Night.” Aaltonen’s car (below left) was sold by Bonhams in 2005 for £100,500. I drove another works car in 1966, reporting on it in Safety Fast magazine and again in Sports Car Classics Vol 1. Amazon £3.08. After a number of countries decided rallies at such speeds dangerous, they refused the Royal Motor Union permission to continue it. The Marathon de la Route became a track event on the Nürburgring. The Liège-Rome-Liège reappeared only as a touring classic.

The Motor, week ending September 5 1964

A hard (four) days’ night. Austin-Healey win an even faster Spa-Sofia-Liège rally. Report by Eric Dymock pictures by George Moore.

“The Liège has been getting slack; there were twenty five finishers last year and eighteen the year before.” In 1961 there were eight, thirteen in 1960 and fourteen the year before that. M. Garot wants it back to about eight and this year he very nearly got his wish until an alteration in plans put several cars back into the running. But he tried.

After the finish, John Sprinzel said, “This year we did about a day and a half's route in a day.” The pace was much, much hotter with average speeds of 50 and 60 mph over rough, rocky roads where such a schedule is just not possible. The 1964 Spa-Sofia-Liège was run in hot weather over roads little rougher than before but at a cracking, damaging pace for four days and nights of the most intensive high-speed motoring in the world.

RaunoAaltonen, the Finnish speedboat racer and Tony Ambrose, Hampshire shopkeeper, won with a works Austin-Healey 3000. Saabs driven by Erik Carlsson and Pat Moss-Carlsson were second and fourth, and Eugene Böhringer took third place in a 230SL Mercedes-Benz after two successive wins in 1962 and 1963. For finishing in three consecutive years, Böhringer wins a Gold Cup in company, this year, with Paul Colteloni (Citroën), Francis Charlier (Volvo) and Bill Bengry (Rover two years, now Sunbeam).

Citroën were the only manufacturer with a team left intact (they had entered three) and none of the club teams finished with more than two runners. Forty-two tired, dusty people steered twenty-one tired, dusty, battered motor¬cars into the finish on Saturday, survivors of the hundred or so gleaming machines which left Belgium late the previous Tuesday. Three Alfa Romeos were entered; none finished. Thirteen Citroëns were entered; only four sighed and wheezed into the last control. Out of eighteen Fords only three survived and the entire Triumph, Renault and Rover teams were. wiped out. Volks¬wagens, usually stayers on rough courses, started with seven, finished with one; even the might of Mercedes was reduced from five to two, although two more struggled on till the very last night.

The scrutineering on Tuesday morning was a leisurely affair, and nothing caused much trouble. As last year, there was some carping over lights, the officials preferring paired spot lamps and reversing lights worked by the gear 1ever and not a switch. So while they appeared not to notice Perspex windows and plastic body panels, they banned an odd fog light. Drivers solemnly removed the bulbs, the officials daubed paint here and there, stamped the car and it was over -¬ except for the replacement of the bulbs just down the road. All very casual. One British team chief wryly remarked “You could drive up here in a supercharged plastic van and they'd pass it”.

The cars were despatched from Liège on Tuesday evening (with the exception of eight non-starters including Trautmann (Lancia) and Feret’s Renault) in quick, three-minute batches of three to spend the night on the Autobahn through Germany, arriving just after first light at Neu Ulm, beyond Stuttgart. The section was neutralized for time, but it was here that Rover's misfortunes began. Anne Hall handed over the 2000 to co-driver Denise McCluggage who, while Anne slept, wrong-slotted down the Stuttgart Auto¬bahn and went 100 kilometres before she realized her mistake. The hour’s lateness guillotine swept down on the Rover before the event was properly under way.

Through Austria, and into northern Italy over the Passo di Resia to the Passo di Xomo, the rally began in earnest. High average speeds were imposed over the dusty, narrow roads, which climbed close to the peaks in everlasting hairpin bends. And the retirements began. The Boyd/Crawford Humber went out before the Alps, so did the Michael Nesbitt/Sheila Aldersmith Mini-Cooper, at Lindau with a broken fan pulley. High in the Alps, at Tresche-Conca the pace and the sun were both hot and tourists coming the other way, through the control at Enego were picking their .way carefully. But enthusiastic Italian policemen waved the rally cars through villages and the popu¬lation joined in urging the drivers to greater things. If the rally was momentarily unpopular with other cars actually on the road, bystanders in those high-altitude villages loved it. (Below: My 1966 works car on test)

By Villa Dont, just before the Yugoslav border, the WiIlcox-Smith Saab retired, the Xomo had claimed an Italian-entered Maserati, and some really punishing sections began. By the time the rally had entered Yugoslavia and passed through Bled, Col and Carrefour Ogulin in the early hours of Thursday morning the pace was telling very seriously. Ford's troubles began with the Richards/David Cortina going out, followed by the Ray/Hatchett Cortina. The Martin Hurst/Bateman Rover 3-litre retired after a stone damaged the fan, which disintegrated through the radiator. The car lost its water and that was that. The Belgian Harris/Gaban Lancia Flaminia, de Lageneste/du Genestou in their works Citroën, the Wilson/Smith Renault, and the Slotemaker/Gorris Daf, were among the 25 cars this 150-mile stretch of rocky, dusty road claimed. Timo Makinen had persistent tyre trouble; six punctures in quick succession losing him so much time he had to retire and another works Citroën went out with clutch trouble. Both American Ford Mustangs retired on this stretch, one overturned.

Novi, on the coast, Zagreb and the autoput to Belgrade then took their toll. The weather remained hot, wearing out tyres and brakes fast, as well as the drivers. The high speeds on the autoput overheated the gearboxes on the heavily undershielded works M.G. Bs of Pauline Mayman/Valerie Domleo and Julian Vernaeve/David Hiam; both broke before Belgrade. The Clark/Culcheth Rover 2000 stopped with engine trouble and the Marang/”Ponti” works Citroën retired. Many, many cars were now running very late and just before the Bulgarian border the organizers intro¬duced a change of route. This added a loop of fairly easy road about 90 kilo¬metres long, with which went a two-hour time allowance. Whether M. Garot did this to give the drivers some breathing space or not, this was in effect what happened and probably more cars reached the finish as a result. Certainly, the original route was passable (some used it) and service crews at Sofia, the turning point, were glad of the extra few minutes to restore the battered cars to something nearer rallyworthiness.

But Bulgaria claimed its victims too. Renault lost two R8s and Austin-Healey the Paddy Hopkirk/Henry Liddon car, which broke down also with gearbox trouble. Honda, after their tragic Liège last year, had entered one car with a Belgian/Japanese crew, but it, too retired when it was hit by a lorry. The Seigle-Morris/Nash Ford Corsair went out at Sofia and so did one of the big rear-engined Czechoslovac Tatras.

The survivors now attacked one of the roughest parts of the entire rally. Back into Yugoslavia through Kursumlija to Titograd and Stolac. The King/Marlow Ford Cortina (a private entry which usually gets further than most) went out near Titograd after the electrics failed and the car had to be push started at every control. A puncture when the time allowance was running out was the final blow. The Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina's front suspension was getting tattered by now and needed frequent attention. Help was recruited from the most unlikely sources to weld and rebuild for a harrowing but apparently hilarious limp to the finish.

The Taylor/Melia works Cortina finished, its rally on the same road, or rather off the same road too badly damaged to continue. SimiIarly the Elford/Stone works Cortina crashed with its wheeIs in the air and the James/ Hughes Rover 3-litre stopped against the rocks, thus sacrificing two gold cups. All the accidents were without serious injury to the drivers.

The Gendebien/Demortier Citroën re¬tired less spectacularly but just as effectively with distributor trouble, then it was the turn of the works Triumph 2000s to fail. They had been going very strongly indeed up to Stolac and Split on the return through Yugoslavia, especially the Terry Hunter/Geoff Mabbs car. The Fidler/Grimshaw and the Thuner/Gretener cars went out first, then the third at Split, all within a short dis¬tance of one another with the rear suspension breaking loose. Logan Morrison/Johnstone Syer retired their works Rover 2000 when they went to the help of the Blomquist/Nilsson Volks¬wagen which had overturned. The driver was unconscious and no other help was available (nobody else, not even a VW team-mate had stopped) so Logan's chances went with another car's acci¬dent. The last Rover (the Cuff/Baguley 3-litre) retired, running out of time after hitting a wall near Split. The Toivonen Volkswagen went out with a broken gearbox.

At Obrovac, the rally had spread itself out over many miles of road. The sur¬vivors who were motoring strongest in the intense heat were being led by the Aaltonen/Ambrose Austin-Healey and Böhringer/Kaiser Mercedes-Benz 230SL, bent now and losing oil. The two Saabs were crackling their fierce exhaust notes through the tiny Yugoslav villages watched by wondering peasants and only Ewy Rosquist looked cool at the wheel of the Mercedes-Benz 220SE she co-drove with Schiek, The long, straggling field drove up the twisty, spectacular, but well¬ surfaced coast road beside the inviting Adriatic and back into the Italian Alps for the second time and the final, gruelling night’s drive. Further casualties were few; there weren’t many cars left to drop out and those who had motored thus far were very determined indeed. A Belgian Mercedes-Benz 220SE failed at Bienno and the similar works car of Kreder and Kling at Trafoi.

The finish was almost an anti-climax. Large crowds and flowers greeted the dusty, battered, straggling cars as they creaked into Spa before the final proces¬sion to the Royal Motor Union premises in Liège itself. Past winner Pat Moss and her pert, pretty 19-year-old Swedish co¬driver Elizabeth Nystrom got a special cheer. The winning Austin-Healey looked little the worse for its ordeal and so did the Saabs. Böhringer's Mercedes had lost some front lights. The brave La Trobe/Skeffington Humber Super Snipe whose, performance had been staggering had a dented door; the big, yellow Tatra V8 which had done equally well (such big cars must have been a handful) was similarly bent. The Alan Allard/Mackies Cortina was scraped on all four corners, after an off-the-road excursion on its roof, and the Sprinzel/Donnegan Cortina limped into the finish using up so much of its time allowance that all the crowds had gone home and no one saw its bruises.

What pleased B.M.C. team manager Stuart Turner almost as much as his out¬right Austin-Healey win? “We broke the sound barrier - we got a Mini to the finish of the Liège.” The Wadsworth/Wood Morris-Cooper was, in the final pare fermé in Belgium, albeit with heavy penalties, but after some 3,100 of the world’s toughest, roughest, fastest miles.

Friday 22 August 2014

Fuel consumption tests

They are trying to change the rules for “official” fuel consumptions. Like the recent yes-no diesel fiasco it’s another example of a politicians’ fix. They created what they thought was an equable system, then discovered they really didn’t know what they were doing. As a road tester I found out how difficult it was to measure fuel consumption accurately. Frugal little saloons gulped fuel driven fast. Gas-guzzlers were surprisingly economical going slowly.

In the 1970s legislators decreed that manufacturers had been telling lies. A formula for working out fuel consumption was no easier for an official mind to work out than mine had been. A single mpg wouldn’t do. There had to be one at a steady slow speed, one at a steady motorway speed and one in traffic. It never worked very well. A slow-speed fuel-sipper could be a gushing drain going fast. Low-geared economy cars could be disappointing in town. A high-geared one could flatter only to deceive on the open road. Introducing Urban Cycle and Extra-Urban Cycle didn’t help much.

Even officials admit the figures are obtained under specific test conditions, “…and may not be achieved in ‘real life’ driving. A range of factors influence actual fuel consumption, driving style and behaviour, as well as the environment. Different variants or versions of one model are grouped together so the figures should be treated as indicative only.”

Averaging out the figures didn’t help. Last year testers were discovered taping up car doors and windows and driving on artificially smooth surfaces to gain a drop in “official” CO2 emissions, linked with fuel consumptions. Now, according to an anonymous EU official who blabbed to Automotive News, proposals for “a new real-world testing method,” are expected this year.

In the 1970s legislators decreed that manufacturers had been telling lies. A formula for working out fuel consumption was no easier for an official mind to work out than mine had been. A single mpg wouldn’t do. There had to be one at a steady slow speed, one at a steady motorway speed and one in traffic. It never worked very well. A slow-speed fuel-sipper could be a gushing drain going fast. Low-geared economy cars could be disappointing in town. A high-geared one could flatter only to deceive on the open road. Introducing Urban Cycle and Extra-Urban Cycle didn’t help much.

Even officials admit the figures are obtained under specific test conditions, “…and may not be achieved in ‘real life’ driving. A range of factors influence actual fuel consumption, driving style and behaviour, as well as the environment. Different variants or versions of one model are grouped together so the figures should be treated as indicative only.”

Averaging out the figures didn’t help. Last year testers were discovered taping up car doors and windows and driving on artificially smooth surfaces to gain a drop in “official” CO2 emissions, linked with fuel consumptions. Now, according to an anonymous EU official who blabbed to Automotive News, proposals for “a new real-world testing method,” are expected this year.

Tuesday 19 August 2014

Deft design at Jaguar

Jaguars inspired designers beyond Jaguar, but none had the certain touch of Sir William Lyons. Bertone, Pininfarina and Giugiaro never matched Jaguar’s founder for identifying Jaguar customers. They were Italian of course. Jaguars were essentially English and middle class. From sunburst upholstery and faux nautical ventilators of the 1920s SS, to lookalike Bentleys of the 1940s Lyons understood his clientele. He provided them with big headlamps and walnut interiors, good proportions and discreet understatement. Jaguars looked not-too-racy and in perfect taste. His skill rarely deserted him although he probably over-embellished his second thoughts. No XK 140 or 150 matched the purity of the XK 120. Later E-types never had the plain elegance of the 1961 original, much the work of aerodynamicist Malcolm Sayer.

It all went wrong with the XJ-S, also partly Sayer’s, and made uncharacteristically with advice from fashionistas, who encouraged square headlamps, and salesmen pushing Jaguar up-market.

Nuccio Bertone had a go in 1957 with a car based on the XK150. The effect was quite close to the Jaguar idiom and in 1966 he did a nicely proportioned 2-door coupe on an S-type saloon. It looked a bit like the Sunbeam Venezia by Superleggera Touring three years earlier launched, if that’s the word, with gondolas in Venice. Pininfarina’s 1978 XJ-S Spyder was a stretchy E-type and William Towns tried an origami one sadly no more successful than his knife-edge Lagonda.

Giugiaro had a go in 1990 with the Kensington based on an XJ12 platform, shown at Geneva, which in my 11 March Sunday Times column I thought important. Jaguar style at the time was being obliged to address a wider market than the English middle class. Giugiaro occupied the high ground of automotive haute couture in 1990, with big commissions from the Far East as well as a series of VWs and Alfa Romeos in Europe. It was deceptive. Giugiaro was never into voluptuous curves and his Jaguar was heavy and rotund. Detailing was good. The grille and classically Jaguar rear window were fine but it remained a one-off. There was no encouragement from Jaguar, which regarded it very much as ‘not invented here’. Bertone tried again in 2011 with a slender pillarless saloon, the B99 hybrid.

The inhibitions designers face now make anything profound or distinctive in car design next to impossible. Crumple zones, pedestrian impact rules and headlamp heights are so constricting that anything ground-breaking is unlikely. Jaguar head of design Ian Callum’s hand is far more repressed than ever Lyons’s or Sayer’s was. Committees lobbyists and legislators, mostly now in Brussels, call the tune. Customers play second fiddle.

Pictures: (top) Sir William Lyons (left) with Tazio Nuvolari, XK120, Silverstone. (Top right) Bertone XK150. (left) Pininfarina XJ41. right Bertone's "Venezia" and left Giugiaro's Kensington. Below Pillarless hybrid at Geneva.

It all went wrong with the XJ-S, also partly Sayer’s, and made uncharacteristically with advice from fashionistas, who encouraged square headlamps, and salesmen pushing Jaguar up-market.

Nuccio Bertone had a go in 1957 with a car based on the XK150. The effect was quite close to the Jaguar idiom and in 1966 he did a nicely proportioned 2-door coupe on an S-type saloon. It looked a bit like the Sunbeam Venezia by Superleggera Touring three years earlier launched, if that’s the word, with gondolas in Venice. Pininfarina’s 1978 XJ-S Spyder was a stretchy E-type and William Towns tried an origami one sadly no more successful than his knife-edge Lagonda.

Giugiaro had a go in 1990 with the Kensington based on an XJ12 platform, shown at Geneva, which in my 11 March Sunday Times column I thought important. Jaguar style at the time was being obliged to address a wider market than the English middle class. Giugiaro occupied the high ground of automotive haute couture in 1990, with big commissions from the Far East as well as a series of VWs and Alfa Romeos in Europe. It was deceptive. Giugiaro was never into voluptuous curves and his Jaguar was heavy and rotund. Detailing was good. The grille and classically Jaguar rear window were fine but it remained a one-off. There was no encouragement from Jaguar, which regarded it very much as ‘not invented here’. Bertone tried again in 2011 with a slender pillarless saloon, the B99 hybrid.

The inhibitions designers face now make anything profound or distinctive in car design next to impossible. Crumple zones, pedestrian impact rules and headlamp heights are so constricting that anything ground-breaking is unlikely. Jaguar head of design Ian Callum’s hand is far more repressed than ever Lyons’s or Sayer’s was. Committees lobbyists and legislators, mostly now in Brussels, call the tune. Customers play second fiddle.

Pictures: (top) Sir William Lyons (left) with Tazio Nuvolari, XK120, Silverstone. (Top right) Bertone XK150. (left) Pininfarina XJ41. right Bertone's "Venezia" and left Giugiaro's Kensington. Below Pillarless hybrid at Geneva.

Friday 15 August 2014

Doubts on Diesels

We should have known better. Take politicians’ encouragement for diesels, then about-facing to say no diesels are really bad. They never say oh we’ve changed our mind or anything and Very Sorry. Boris and the rest of them are quite impenitent, They are going to charge diesels more whenever they get the chance.

It was so predictable. It’s not simply that politicians are self-serving, we can all be self-serving, but they just look so stupid. There seemed to be votes in going along with diesels in the 1990s when they could sell them on the back of “environmental” opinion. They may even have thought they were doing the “right” thing. People voting for them maybe believed it too. We in the media told them, quite often as it happens 25-30 years ago, that they were barking up a wrong tree. I liked diesels. They didn’t need sparks and electricity, which always gave trouble in the cars I could afford but they were never clean. Diesel was a byword for soot and smoke.

We, and I mean in this case me and many others, were far more convinced about the merit of lean-burn petrol engines rather than the catalytic converters about which lobbyists had convinced the politicos. It was the same with diesels. They’re sooty, we told them. Particulates are bad and you’ll be sorry, which they now are of course even though they can’t use the word. They listened to noble metals lobbyists and “environmentalists” panicking about global warming and CO2.

The “greenhouse effect” had been scary for years. In the 1960s I suppose, I had read a cautionary paper about it written by somebody I respected. I half-believed in it myself. There were motor industry people I trusted who apparently believed in it as well. I felt obliged to take it seriously and it was years before it became apparent that it was the greatest scientific fraud in the history of the planet.

It wasn’t so much that I was in denial about global warming, as increasingly sceptical about the alarmist messages over its cause. In the 1980s I remained open-minded. But what the reality was, as revealed to me years later by the head of research at Mercedes-Benz, was that industry engineers were only acknowledging a movement bound to enrapture politicians, much as they had in the Los Angeles smogs of the 1950s. The motor industry knew it would have to pay lip-service to greenery and for decades it was forced to continually reinvent “solutions” to appease political vanity. Engineers, it turns out, were more concerned with meeting the demands of legislatures than ever they were about man-made global panic-mongering.

Dr Thomas Weber was a member of the Board of Management of Daimler AG, and responsible for Group Research & Mercedes-Benz cars’ development. He told me Daimler was spending €4.4 billion every year guessing what wheeze the politicians would decide on next. Throughout Europe they were obsessed with climate change or safety or whatever cause celebre lobbyists were coming up with.

And now, with diesels, they have changed their mind. Why am I not surprised?

Pictures (top): Not a diesel 1. 1940 BMW 328, tall 2 litre with three downdraught carburettors. OZ80 on cam cover denotes racing engine of Mille Miglia car I drove on Scottish event. (right)

First production diesel car, Mercedes-Benz 260D 1936-1939. (left) And its engine. (Below) Not a diesel 2 Mercedes-Benz test track, Unterturkheim, not as scary as it looks, I drove identical car here with test driver instructing precisely on speed and place on the banking.

It was so predictable. It’s not simply that politicians are self-serving, we can all be self-serving, but they just look so stupid. There seemed to be votes in going along with diesels in the 1990s when they could sell them on the back of “environmental” opinion. They may even have thought they were doing the “right” thing. People voting for them maybe believed it too. We in the media told them, quite often as it happens 25-30 years ago, that they were barking up a wrong tree. I liked diesels. They didn’t need sparks and electricity, which always gave trouble in the cars I could afford but they were never clean. Diesel was a byword for soot and smoke.

We, and I mean in this case me and many others, were far more convinced about the merit of lean-burn petrol engines rather than the catalytic converters about which lobbyists had convinced the politicos. It was the same with diesels. They’re sooty, we told them. Particulates are bad and you’ll be sorry, which they now are of course even though they can’t use the word. They listened to noble metals lobbyists and “environmentalists” panicking about global warming and CO2.

The “greenhouse effect” had been scary for years. In the 1960s I suppose, I had read a cautionary paper about it written by somebody I respected. I half-believed in it myself. There were motor industry people I trusted who apparently believed in it as well. I felt obliged to take it seriously and it was years before it became apparent that it was the greatest scientific fraud in the history of the planet.

It wasn’t so much that I was in denial about global warming, as increasingly sceptical about the alarmist messages over its cause. In the 1980s I remained open-minded. But what the reality was, as revealed to me years later by the head of research at Mercedes-Benz, was that industry engineers were only acknowledging a movement bound to enrapture politicians, much as they had in the Los Angeles smogs of the 1950s. The motor industry knew it would have to pay lip-service to greenery and for decades it was forced to continually reinvent “solutions” to appease political vanity. Engineers, it turns out, were more concerned with meeting the demands of legislatures than ever they were about man-made global panic-mongering.

Dr Thomas Weber was a member of the Board of Management of Daimler AG, and responsible for Group Research & Mercedes-Benz cars’ development. He told me Daimler was spending €4.4 billion every year guessing what wheeze the politicians would decide on next. Throughout Europe they were obsessed with climate change or safety or whatever cause celebre lobbyists were coming up with.

And now, with diesels, they have changed their mind. Why am I not surprised?

Pictures (top): Not a diesel 1. 1940 BMW 328, tall 2 litre with three downdraught carburettors. OZ80 on cam cover denotes racing engine of Mille Miglia car I drove on Scottish event. (right)

First production diesel car, Mercedes-Benz 260D 1936-1939. (left) And its engine. (Below) Not a diesel 2 Mercedes-Benz test track, Unterturkheim, not as scary as it looks, I drove identical car here with test driver instructing precisely on speed and place on the banking.

Wednesday 13 August 2014

Footballers' cars

Earning £31,000 a week you could buy a new Range Rover every fortnight. Yet fifty Premier League footballers are having to borrow the money. Oracle, which describes itself as a luxury finance broker, says players use Oracle Finance as a tax-efficient way of buying supercars. The broker’s insight into super-rich sports stars’ buying habits shows most of them go for Range Rovers. The average Premier League player, according to Deloitte’s annual review earns £1.6 million; the top clubs’ combined salary bill is over £1.78billion. Manchester City’s wage bill alone is £233million. Ahead of the start of the Premiership season this weekend Oracle names football stars’ top 10.

Range Rovers win. Oracle Finance managing director Peter Brook says: “We looked back at our records over the last five years and weren’t surprised the Range Rover was top. We can’t say which footballers use us because of client confidentiality, but we work with some of the biggest names in the footballing world and have helped hundreds of players, managers and agents fund their dream cars.”

The top 10 most popular are:

1 Range Rover 28

2 Bentley Continental GT 26

3 Range Rover Sport 24

4 Audi Q7 21

5 BMW X5 18

6 Porsche Cayenne 16

7 Lamborghini Gallardo 13

8 Ferrari 458 8

9 Maserati Gran Turismo 4

10 Aston Martin DB9 3

Mr Brook said: “Bentley was extremely close to taking the number one spot in our Premiership poll with the GT, but it’s clear SUVs are a favourite with footballers. Our clients like their cars to be luxurious with high-up driving positions, which is why they prefer 4x4s to out-and-out supercars. Few cars offer all that like a full-fat Range Rover.”

I drive Range Rovers (top and bottom) at Land Rover’s testing track, Eastnor Castle and (middle) on the 1970 press launch at Goonhilly tracking station. Picture from The Land Rover 65 ebook £8.04 on Amazon

Range Rovers win. Oracle Finance managing director Peter Brook says: “We looked back at our records over the last five years and weren’t surprised the Range Rover was top. We can’t say which footballers use us because of client confidentiality, but we work with some of the biggest names in the footballing world and have helped hundreds of players, managers and agents fund their dream cars.”

The top 10 most popular are:

1 Range Rover 28

2 Bentley Continental GT 26

3 Range Rover Sport 24

4 Audi Q7 21

5 BMW X5 18

6 Porsche Cayenne 16

7 Lamborghini Gallardo 13

8 Ferrari 458 8

9 Maserati Gran Turismo 4

10 Aston Martin DB9 3

Mr Brook said: “Bentley was extremely close to taking the number one spot in our Premiership poll with the GT, but it’s clear SUVs are a favourite with footballers. Our clients like their cars to be luxurious with high-up driving positions, which is why they prefer 4x4s to out-and-out supercars. Few cars offer all that like a full-fat Range Rover.”

I drive Range Rovers (top and bottom) at Land Rover’s testing track, Eastnor Castle and (middle) on the 1970 press launch at Goonhilly tracking station. Picture from The Land Rover 65 ebook £8.04 on Amazon

Tuesday 12 August 2014

Jensen-Healey

It looked as though America was about to ban open cars so a headline writer at The Guardian titled a Jensen-Healey column, “The last open sports car?”. Well, it wasn't; America changed its mind on going topless. Another edition of the newspaper called it a “West Brom Bomb”. Alas, the Jensen-Healey was not as good as real West Bromwich Jensens.

Otherwise the words were accurate and well intentioned. I was careful with a caveat in the first paragraph. My brief half hour's drive was too short for more than a superficial assessment. It was a time, I felt, for hedging bets. I had been unconvinced by Kjell Qvale, the Norwegian-American who made a fortune selling sports cars in California and was by then frustrated. With no beautiful Austin-Healeys to sell he became president of Jensen, made Donald Healey chairman and Geoffrey Healey a director. It lasted until 1973 when Donald resigned, frustrated at the changes between prototype and production, not to mention endemic cam cover oil leaks from the Lotus engine, which had been designed with a dry sump for racing.

There was an unusual problem parking a Jensen-Healey on a hill. Dell'orto carburetor needles allowed petrol to drip into the sump, one of the misfortunes (others included water leaks) that dogged the car throughout its brief production life. Later estate-car versions, known as Jensen GTs, were laden with luxury but weighed down by US safety bumpers. Poundage was up, performance suffered and only 473 were ever made. Total Jensen-Healey production was 10,926 This edition of the newspaper spelt Tony Rudd Tondy Rudd, by way of illustrating why whimsical Fleet Street called it The Grauniad.

MOTORING GUARDIAN, 16 September 1972 ERIC DYMOCK on the new Jensen-Healey sports car. Jensen Motors has put into production the Jensen-Healey announced at the Geneva motor show in March. Production will soon reach 200 a week, with about 60 per cent bound for North America. Coinciding with the start of production, I had a brief, 30 miles’ drive, too short for more than a superficial examination, but enough to suggest that it is going to be a better car than it looked at Geneva.

The philosophy of the Jensen-Healey is straightforward. It is a replacement for the Austin-Healey 3000. A robust sporting car produced by the British Motor Corporation and latterly British Leyland, it dated back to the 100/4 of 1952. The Austin-Healey 100/6 of 1957 was made up till 1969, when American safety regulations made demands it could not meet. The design, by then nearly 20 years old, could not be changed to satisfy the rules and the “Big Healey” that had done so much for BMC and BLMC prestige, winning rallies like the 1961 and 1962 Alpines and the 1964 “Liege”, was dropped. The production line at Jensen in West Bromwich, where Healey bodies had been made, was summarily stopped, and sports car dealers all over America found themselves without one of their best sellers.

One of these dealers was Kjell Qvale, and no sooner had Lord Stokes pronounced sentence on the Healey than Qvale was in Britain negotiating a replacement. British Leyland was not inclined to build it, so to ensure that its subcontractor Jensen would, Qvale stepped on. He brought finance to help the firm over the crisis caused by the loss not only of the Healey, but also the Sunbeam Tiger, which Jensen made under contract for Rootes, later Chrysler. Donald Healey and his son Geoffrey set about the design of a new open 2-seater, and searched for a suitable engine.

The layout of the car sustained Healey’s tradition for strength, making use of as many standard components already in production as possible. The idea was to keep down the cost of development, buying parts cheaply. By motor industry standards, Jensen-Healey quantities are relatively small, but using the same rear suspension links as Vauxhall, which orders them by the 10,000, the Jensen benefits from other manufacturers’ volume production. The engine chosen for the Jensen-Healey was an inclined twin overhead camshaft 4-cylinder Lotus, developed for a sports car not yet announced, designed by former BRM chief engineer, Tony Rudd. This was installed in a Healey-designed body shell as developed by a Jensen team under Kevin Beattie, who had been responsible for the Jensen Interceptor.

Beattie had also been responsible for the brilliant four wheel drive FF, one of the world's safest cars, ironically forced out of production by the same American Federal Safety regulations that threw Austin-Healey production lines into idleness. While the Jensen-Healey is in the mould of the old Austin-Healey as a fast, open sports car in the style of the 1950s, it is completely new. In contrast to the old car's rather ponderous iron 6-cylinder engine, the die-cast aluminium Lotus four is high-revving and responsive. Also a contrast to the heavy steering and stiff gearchange which, in an inverted sense, many owners of the Austin-Healey actually enjoyed because, like exercise, they thought driving a thoroughbred sports car ought to be strenuous, the Jensen-Healey has light steering and an exemplary smooth change with a short crisp movement.

The Jensen-Healey would benefit from slightly firmer springing. It bounces over bumps instead of riding them smoothly but the handling is otherwise good. Acceleration is swift and although there was no chance to see how fast it would go, Jensen's claim of 120mph (193.1kph) will not be wide of the mark. It also claims 24mpg (11.8l/100km), which sounds about right for an efficient 2litre engine in a 2650lb (1202kg) car with low frontal area. The last of the big Healey 3000s had polished woodwork and a quality look about the interior. Alas, safety rules have changed that too and the Jensen-Healey has padded plastic, better to knock your head against, but less elegant. Any colour may be specified for upholstery but all you will get is black. By way of compensation the seats are comfortable, and with reclining backrests they can be adjusted to people of most sizes. Cushions and backrests are shaped to hold occupants in place on corners.

For a sports car in which sacrifices are implied for the pleasure of style or performance, or providing an excuse for leaving someone behind, luggage space is adequate and well shaped without being generous. A fuel capacity of 11gal (50l), giving a range of only just over 250miles (402.3kms) between fillings seems niggardly. If the Jensen-Healey is as rust-resistant and trouble-free as its predecessor and provided the legislators do not force it out of existence this car could keep the workers at West Bromwich in business for another 20 years. Priced in Britain, with tax, £1,810.

It wasn’t rust-resistant or trouble-free and didn’t keep West Brom going for 20 years. The Yom Kippur War of 1973 pulled the plug on Jensen. Sales of the splendid Interceptor slumped. American dealers subscribed briefly to the flawed Jensen-Healey but to no avail. Jensen foundered in 1976 and an unsympathetic Government, which would later subsidise Delorean to the tune of £75,000,000 to buy a few votes and a trifling popularity in Northern Ireland, refused a paltry million to save one of Britain's fine cars. Like MG, Jensen employed good craftsmen, honest workers - but not enough of them to create a political crisis and motivate a bail-out.

Pictures: (from top) Motoring Guardian column. Jensen-Healey 2-seater. Troublesome sloper Lotus engine.

Austin-Healey 100S at Goodwood. Exquisite lines with roll-over protection. Jensen FF II I road tested, still on trade-plates at Hyde Park Corner. Austin-Healey 3000 Mk III.

More on Jensen and Healey in Sports car Classics Vol 1 and Sports Car Classics Vol 2, both £3.08 ebooks

Otherwise the words were accurate and well intentioned. I was careful with a caveat in the first paragraph. My brief half hour's drive was too short for more than a superficial assessment. It was a time, I felt, for hedging bets. I had been unconvinced by Kjell Qvale, the Norwegian-American who made a fortune selling sports cars in California and was by then frustrated. With no beautiful Austin-Healeys to sell he became president of Jensen, made Donald Healey chairman and Geoffrey Healey a director. It lasted until 1973 when Donald resigned, frustrated at the changes between prototype and production, not to mention endemic cam cover oil leaks from the Lotus engine, which had been designed with a dry sump for racing.

There was an unusual problem parking a Jensen-Healey on a hill. Dell'orto carburetor needles allowed petrol to drip into the sump, one of the misfortunes (others included water leaks) that dogged the car throughout its brief production life. Later estate-car versions, known as Jensen GTs, were laden with luxury but weighed down by US safety bumpers. Poundage was up, performance suffered and only 473 were ever made. Total Jensen-Healey production was 10,926 This edition of the newspaper spelt Tony Rudd Tondy Rudd, by way of illustrating why whimsical Fleet Street called it The Grauniad.

MOTORING GUARDIAN, 16 September 1972 ERIC DYMOCK on the new Jensen-Healey sports car. Jensen Motors has put into production the Jensen-Healey announced at the Geneva motor show in March. Production will soon reach 200 a week, with about 60 per cent bound for North America. Coinciding with the start of production, I had a brief, 30 miles’ drive, too short for more than a superficial examination, but enough to suggest that it is going to be a better car than it looked at Geneva.

The philosophy of the Jensen-Healey is straightforward. It is a replacement for the Austin-Healey 3000. A robust sporting car produced by the British Motor Corporation and latterly British Leyland, it dated back to the 100/4 of 1952. The Austin-Healey 100/6 of 1957 was made up till 1969, when American safety regulations made demands it could not meet. The design, by then nearly 20 years old, could not be changed to satisfy the rules and the “Big Healey” that had done so much for BMC and BLMC prestige, winning rallies like the 1961 and 1962 Alpines and the 1964 “Liege”, was dropped. The production line at Jensen in West Bromwich, where Healey bodies had been made, was summarily stopped, and sports car dealers all over America found themselves without one of their best sellers.

One of these dealers was Kjell Qvale, and no sooner had Lord Stokes pronounced sentence on the Healey than Qvale was in Britain negotiating a replacement. British Leyland was not inclined to build it, so to ensure that its subcontractor Jensen would, Qvale stepped on. He brought finance to help the firm over the crisis caused by the loss not only of the Healey, but also the Sunbeam Tiger, which Jensen made under contract for Rootes, later Chrysler. Donald Healey and his son Geoffrey set about the design of a new open 2-seater, and searched for a suitable engine.

The layout of the car sustained Healey’s tradition for strength, making use of as many standard components already in production as possible. The idea was to keep down the cost of development, buying parts cheaply. By motor industry standards, Jensen-Healey quantities are relatively small, but using the same rear suspension links as Vauxhall, which orders them by the 10,000, the Jensen benefits from other manufacturers’ volume production. The engine chosen for the Jensen-Healey was an inclined twin overhead camshaft 4-cylinder Lotus, developed for a sports car not yet announced, designed by former BRM chief engineer, Tony Rudd. This was installed in a Healey-designed body shell as developed by a Jensen team under Kevin Beattie, who had been responsible for the Jensen Interceptor.

Beattie had also been responsible for the brilliant four wheel drive FF, one of the world's safest cars, ironically forced out of production by the same American Federal Safety regulations that threw Austin-Healey production lines into idleness. While the Jensen-Healey is in the mould of the old Austin-Healey as a fast, open sports car in the style of the 1950s, it is completely new. In contrast to the old car's rather ponderous iron 6-cylinder engine, the die-cast aluminium Lotus four is high-revving and responsive. Also a contrast to the heavy steering and stiff gearchange which, in an inverted sense, many owners of the Austin-Healey actually enjoyed because, like exercise, they thought driving a thoroughbred sports car ought to be strenuous, the Jensen-Healey has light steering and an exemplary smooth change with a short crisp movement.

The Jensen-Healey would benefit from slightly firmer springing. It bounces over bumps instead of riding them smoothly but the handling is otherwise good. Acceleration is swift and although there was no chance to see how fast it would go, Jensen's claim of 120mph (193.1kph) will not be wide of the mark. It also claims 24mpg (11.8l/100km), which sounds about right for an efficient 2litre engine in a 2650lb (1202kg) car with low frontal area. The last of the big Healey 3000s had polished woodwork and a quality look about the interior. Alas, safety rules have changed that too and the Jensen-Healey has padded plastic, better to knock your head against, but less elegant. Any colour may be specified for upholstery but all you will get is black. By way of compensation the seats are comfortable, and with reclining backrests they can be adjusted to people of most sizes. Cushions and backrests are shaped to hold occupants in place on corners.

For a sports car in which sacrifices are implied for the pleasure of style or performance, or providing an excuse for leaving someone behind, luggage space is adequate and well shaped without being generous. A fuel capacity of 11gal (50l), giving a range of only just over 250miles (402.3kms) between fillings seems niggardly. If the Jensen-Healey is as rust-resistant and trouble-free as its predecessor and provided the legislators do not force it out of existence this car could keep the workers at West Bromwich in business for another 20 years. Priced in Britain, with tax, £1,810.

It wasn’t rust-resistant or trouble-free and didn’t keep West Brom going for 20 years. The Yom Kippur War of 1973 pulled the plug on Jensen. Sales of the splendid Interceptor slumped. American dealers subscribed briefly to the flawed Jensen-Healey but to no avail. Jensen foundered in 1976 and an unsympathetic Government, which would later subsidise Delorean to the tune of £75,000,000 to buy a few votes and a trifling popularity in Northern Ireland, refused a paltry million to save one of Britain's fine cars. Like MG, Jensen employed good craftsmen, honest workers - but not enough of them to create a political crisis and motivate a bail-out.

Pictures: (from top) Motoring Guardian column. Jensen-Healey 2-seater. Troublesome sloper Lotus engine.

Austin-Healey 100S at Goodwood. Exquisite lines with roll-over protection. Jensen FF II I road tested, still on trade-plates at Hyde Park Corner. Austin-Healey 3000 Mk III.

More on Jensen and Healey in Sports car Classics Vol 1 and Sports Car Classics Vol 2, both £3.08 ebooks

Sunday 10 August 2014

Frank Page

Sad that the irrepressibly optimistic Frank Page has died. The Observer, Mail on Sunday, presenter on Top Gear; his career was wide and his judgements usually fair and precise. He was a joy until strokes and illness dogged him. His enthusiasm was boundless. Meet him at the airport going on a press trip and he would be bubbling over with joy to let you know what Denis Thatcher had just told him during a round of golf. Generous and funny, a worthy Guild Chairman with a keen sense of occasion and a credit to the profession. Another light gone out. Picture: Bentley event at Le Mans.

Thursday 7 August 2014

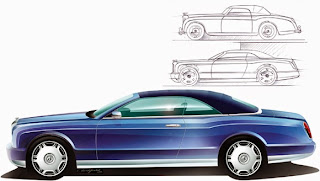

Bentley Azure

Returning Bentley CEO Wolfgang Dürheimer, it seems, waxes nostalgic for a convertible. He’d like to build a 2-seater but he’ll most likely follow Royce’s example and go for a 4-seater. He liked the 1995 Azure, which continued in various iterations for years. His options now, with W12, V8 and V10s available from stock, as it were, are wide and the Continental is a fine platform. The Complete Bentley recalled the first Azure (left).

By 1995, after the best part of a quarter-century, the Corniche-Continental’s time was up. When they drew up Project 90 in 1985, (below) which had evolved into the Continental R, Heffernan and Greenley conceived a convertible which as a result had been waiting ten years. Despite a good deal of strengthening and reinforcement, scuttle shake was endemic in the old Corniche, so it had to be done away with for the Azure. Basing it on the Continental R instead of the old Corniche brought a 25 per cent improvement in torsional stiffness.

Manufacture however was not straightforward. A joint project was arranged between Crewe and Pininfarina in Turin under which Park Sheet Metal in Coventry, which made Continental R body shells, sent sub-assemblies to Italy for completed bodies to be painted and have the intricate power-operated hood mechanism fitted by specialist Opac before being shipped back to Crewe for completion. Bodybuilding was done at Pininfarina’s San Giorgio Canavese factory, where Cadillac Allantes had been put together. The unitary hulls still had to be strengthened to make up for the absence of a roof, with an additional 190kg (418.9lb) of reinforcement under the rear floor, deeper door sills, thicker A-posts and screen top rail.

All that remained of the Corniche’s shivers, I recall from a 1995 road test, were tremors that could still be seen in the rear-view mirror and vibrations felt through the steering column. Door sill plates proclaimed Bentley Motors’ and Pininfarina credit for the structure, in particular the power hood designed to close in 30sec, although one famously failed on the Cote d’Azur press launch. The Azure’s interior was furnished like the Continental R with traditional veneers and leather, woollen fleeces on the floor and, by virtue of a 1992 co-operative agreement with BMW, electrically operated front seats with integral seat belts from the 8-series coupe.Final Azure 2005

Several generations of fast turbocharged Bentleys had transformed road behaviour, from the early tentative 1970s when Bentleys carried the legacy of Rolls-Royce town carriages, to the dawn of the 21st century when they were more able to compete with fast rivals. Steering was now 2.9 turns from lock to lock, faster, sharper, with more feel; braking more progressive with ever-bigger discs, and body roll, although by no means eliminated was less pronounced.

INTRODUCTION Geneva 1995.BODY Convertible; 2-doors, 4 -seats; weight 2610kg (5754lb);

ENGINE V8-cylinders, in-line; front; 104.1mm x 99.1mm, 6750cc; compr 8:1; 286kW (383.53bhp) @ 4000rpm; 42.4kW (56.86bhp)/l; 750Nm (553lbft) @ 2000rpm. ENGINE STRUCTURE pushrod overhead valves; hydraulic tappets; gear-driven central cast iron camshaft; aluminium silicon cylinder head; steel valve seats, aluminium-silicon block; cast iron wet cylinder liners; Garrett AiResearch TO4 turbocharger .5bar (7.25psi); intercooler; Zytek EMS3 motormanagement; 5-bearing chrome molybdenum crankshaft. TRANSMISSION rear wheel drive; GM turbo Hydramatic 4-speed; final drive 2.69:1 CHASSIS steel monocoque, front and rear sub-frames; independent front suspension by coil springs and wishbones; anti roll bar; independent rear suspension by coil springs and semi-trailing arms; Panhard rod stiffener; anti roll bar; three-stage electronically controlled telescopic dampers and Boge pressure hydraulic self-levelling; hydraulic servo brakes, 27.94cm (11in) dia discs front ventilated; twin circuit; Bosch ABS; rack and pinion PAS; l08l (23.75gal) fuel tank; 255/55-WR 17 tyres, 7.6in rims, cast alloy wheels DIMENSIONS wheelbase 306cm (120.47in); track 155cm (61.02in); length 534cm (210.24in); width 188cm (74.02in); height 146cm (57.48in); ground clearance 14cm (5.5in); turning circle 13.1m (42.98ft).EQUIPMENT 2-level air conditioning, leather upholstery, pile carpet, 8-way electric seat adjustment, galvanised underbody PERFORMANCE maximum speed 249kph (155.1mph); 64kph (39.87mph) @ 1000rpm; 0-100kph (62mph) 6.0sec; fuel consumption 19.3l/100km (14.64mpg) PRICE £215,000 PRODUCTION 1311

PICTURES above right 2003 Limited Azure edition. Left Road test GTC chez nous

By 1995, after the best part of a quarter-century, the Corniche-Continental’s time was up. When they drew up Project 90 in 1985, (below) which had evolved into the Continental R, Heffernan and Greenley conceived a convertible which as a result had been waiting ten years. Despite a good deal of strengthening and reinforcement, scuttle shake was endemic in the old Corniche, so it had to be done away with for the Azure. Basing it on the Continental R instead of the old Corniche brought a 25 per cent improvement in torsional stiffness.

Manufacture however was not straightforward. A joint project was arranged between Crewe and Pininfarina in Turin under which Park Sheet Metal in Coventry, which made Continental R body shells, sent sub-assemblies to Italy for completed bodies to be painted and have the intricate power-operated hood mechanism fitted by specialist Opac before being shipped back to Crewe for completion. Bodybuilding was done at Pininfarina’s San Giorgio Canavese factory, where Cadillac Allantes had been put together. The unitary hulls still had to be strengthened to make up for the absence of a roof, with an additional 190kg (418.9lb) of reinforcement under the rear floor, deeper door sills, thicker A-posts and screen top rail.

All that remained of the Corniche’s shivers, I recall from a 1995 road test, were tremors that could still be seen in the rear-view mirror and vibrations felt through the steering column. Door sill plates proclaimed Bentley Motors’ and Pininfarina credit for the structure, in particular the power hood designed to close in 30sec, although one famously failed on the Cote d’Azur press launch. The Azure’s interior was furnished like the Continental R with traditional veneers and leather, woollen fleeces on the floor and, by virtue of a 1992 co-operative agreement with BMW, electrically operated front seats with integral seat belts from the 8-series coupe.Final Azure 2005

Several generations of fast turbocharged Bentleys had transformed road behaviour, from the early tentative 1970s when Bentleys carried the legacy of Rolls-Royce town carriages, to the dawn of the 21st century when they were more able to compete with fast rivals. Steering was now 2.9 turns from lock to lock, faster, sharper, with more feel; braking more progressive with ever-bigger discs, and body roll, although by no means eliminated was less pronounced.

INTRODUCTION Geneva 1995.BODY Convertible; 2-doors, 4 -seats; weight 2610kg (5754lb);

ENGINE V8-cylinders, in-line; front; 104.1mm x 99.1mm, 6750cc; compr 8:1; 286kW (383.53bhp) @ 4000rpm; 42.4kW (56.86bhp)/l; 750Nm (553lbft) @ 2000rpm. ENGINE STRUCTURE pushrod overhead valves; hydraulic tappets; gear-driven central cast iron camshaft; aluminium silicon cylinder head; steel valve seats, aluminium-silicon block; cast iron wet cylinder liners; Garrett AiResearch TO4 turbocharger .5bar (7.25psi); intercooler; Zytek EMS3 motormanagement; 5-bearing chrome molybdenum crankshaft. TRANSMISSION rear wheel drive; GM turbo Hydramatic 4-speed; final drive 2.69:1 CHASSIS steel monocoque, front and rear sub-frames; independent front suspension by coil springs and wishbones; anti roll bar; independent rear suspension by coil springs and semi-trailing arms; Panhard rod stiffener; anti roll bar; three-stage electronically controlled telescopic dampers and Boge pressure hydraulic self-levelling; hydraulic servo brakes, 27.94cm (11in) dia discs front ventilated; twin circuit; Bosch ABS; rack and pinion PAS; l08l (23.75gal) fuel tank; 255/55-WR 17 tyres, 7.6in rims, cast alloy wheels DIMENSIONS wheelbase 306cm (120.47in); track 155cm (61.02in); length 534cm (210.24in); width 188cm (74.02in); height 146cm (57.48in); ground clearance 14cm (5.5in); turning circle 13.1m (42.98ft).EQUIPMENT 2-level air conditioning, leather upholstery, pile carpet, 8-way electric seat adjustment, galvanised underbody PERFORMANCE maximum speed 249kph (155.1mph); 64kph (39.87mph) @ 1000rpm; 0-100kph (62mph) 6.0sec; fuel consumption 19.3l/100km (14.64mpg) PRICE £215,000 PRODUCTION 1311

PICTURES above right 2003 Limited Azure edition. Left Road test GTC chez nous

Tuesday 5 August 2014

No small slow coach

Thirteen seconds to reach 60 sounds slow. A Fiat 1500 was “lively” when the likes of a Ford Classic took 25sec. Half a minute was by no means uncommon, so I was worried that the 1 litre Ford EcoSport might feel like back to the 1970s. Really it didn’t. It will do 112mph, 20mph faster than the Fiat and 30mph more than the Classic. It also does 40 to 60mpg, two or three times what they could, and with 125PS has more than twice their power.

The EcoSport is a mini-sports utility, or a compact crossover depending on what jargon you prefer. It is chunky, looks the part, high off the ground like a grown-up SUV. There was no chance to try it off-road but it will be fine on the grass at school sports days. It has a 10.6m (34.8ft) turning circle, real front and rear skid plates, 18cm (7in) ground clearance, a 22.1deg approach angle and 35deg departure and it can wade up to 55cm (21.6in). Ford says the full-size spare wheel is hung out the back to give more luggage room although it looks more ornamental for school run street cred. There’s a neat cover yet it does make the back door heavy.

It may be built in India on a Fiesta platform but EcoSport was developed in South America. A global Ford introduced in 2003, it is credited with creating the mini-SUV segment in Brazil, has sold more than 770,000 and will now satisfy the same trend in Europe. Ford expects all SUVs to go up nearly a quarter this year, and small ones like this to increase by 90 per cent by 2018.

It is well proportioned and looks cheerful although at £16,000 scarcely cheap. Good value rather than bargain basement, our EK14 XNM had the Kinetic Blue metallic paint at £495, rear parking sensors at £210 and something called SYNC with APPLINK giving voice control of smartphone apps. Useful built-in extras include ABS, electronic stability and traction controls, tyre pressure monitoring and smart roof rails for an all-in £16,500.

There is an alternative 112PS 1.5 litre petrol engine of 44.8mpg and 149g/km CO2, or a 90PS 1.5-litre TDCi diesel that does 61.4mpg and 120g/km. But with the clever little turbocharged 1.0’s 53.3mpg and 125g/km CO2 there seems little point in bypassing it unless you want an automatic. I wonder if they’ll do a 4x4 to challenge the established Orientals?

Stylish and practical with a short bonnet, raked front pillars, and five-piece chrome grille it has angular headlamps and LED light strips. The driver sits tall, on a seat height adjustable with a steering column adjustable for reach and rake. There is good headroom and legroom and befitting an SUV with outdoor overtones it has 20 stowage places, including door pockets with space for large drinks bottles, a drawer under the front passenger seat, and a cooled glove box that can take six 350ml cans.

Occasion for driving the EcoSport was the Association of Scottish Motoring Writers’ annual presentation of the Jim Clark Memorial Trophy. There was a certain poignancy this year following the fatal accident to bystanders on the Jim Clark Rally for its presentation to Dr John Harrington in recognition of his 30 years’ work, raising medical standards and improving safety at rallies in Scotland. Alisdair Suttie (right of picture), Association President, said: “At a time when rally safety is in the spotlight, we were pleased to present this year’s Award to a medically qualified winner. Dr Harrington demonstrates the planning and preparation in motorsport events, the high levels of expertise available to competitors and the professionalism that swings into action when required.”

The EcoSport is a mini-sports utility, or a compact crossover depending on what jargon you prefer. It is chunky, looks the part, high off the ground like a grown-up SUV. There was no chance to try it off-road but it will be fine on the grass at school sports days. It has a 10.6m (34.8ft) turning circle, real front and rear skid plates, 18cm (7in) ground clearance, a 22.1deg approach angle and 35deg departure and it can wade up to 55cm (21.6in). Ford says the full-size spare wheel is hung out the back to give more luggage room although it looks more ornamental for school run street cred. There’s a neat cover yet it does make the back door heavy.

It may be built in India on a Fiesta platform but EcoSport was developed in South America. A global Ford introduced in 2003, it is credited with creating the mini-SUV segment in Brazil, has sold more than 770,000 and will now satisfy the same trend in Europe. Ford expects all SUVs to go up nearly a quarter this year, and small ones like this to increase by 90 per cent by 2018.

It is well proportioned and looks cheerful although at £16,000 scarcely cheap. Good value rather than bargain basement, our EK14 XNM had the Kinetic Blue metallic paint at £495, rear parking sensors at £210 and something called SYNC with APPLINK giving voice control of smartphone apps. Useful built-in extras include ABS, electronic stability and traction controls, tyre pressure monitoring and smart roof rails for an all-in £16,500.

There is an alternative 112PS 1.5 litre petrol engine of 44.8mpg and 149g/km CO2, or a 90PS 1.5-litre TDCi diesel that does 61.4mpg and 120g/km. But with the clever little turbocharged 1.0’s 53.3mpg and 125g/km CO2 there seems little point in bypassing it unless you want an automatic. I wonder if they’ll do a 4x4 to challenge the established Orientals?

Stylish and practical with a short bonnet, raked front pillars, and five-piece chrome grille it has angular headlamps and LED light strips. The driver sits tall, on a seat height adjustable with a steering column adjustable for reach and rake. There is good headroom and legroom and befitting an SUV with outdoor overtones it has 20 stowage places, including door pockets with space for large drinks bottles, a drawer under the front passenger seat, and a cooled glove box that can take six 350ml cans.